These are the replacement bridges for the two that were burned during the Jones-Imboden Raid.

Jones-Imboden Raid in Doddridge County

On April 20, 1863 President Abraham Lincoln signed the proclamation that gave his formal approval to the admission of West Virginia as the 35th state of the Union. Immediately after that, Confederate forces, under the command of William E. “Grumble” Jones and John D. Imboden, embarked on a month-long raid through West Virginia aimed at disabling the B&O and other railroads, disrupting the Union government at Wheeling, and capturing horses, cattle and supplies. On May 6th, 1863, those forces entered Doddridge County, one of their primary targets being the railroad bridge over the Middle Island Creek in West Union. That bridge, which we now know as the one overlooking the dam near the football field, was the longest and highest train bridge on the Parkersburg branch of the railroad.

Through newspaper articles and documents in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, I’ve been able to piece together a fair representation of what happened that day.

Union Forces Arrive

On May 4th, while encamped at Bridgeport, Col. George Latham of the 2nd W.Va. Infantry received word from the War (Middle) Department to proceed to West Union because General Jones had sent a group of rebels that way looking to destroy the railroad bridges over the Middle Island Creek. Col. Latham immediately brought six companies with him and arrived at West Union at 3:00 a.m. on the morning of May 5th. During the morning of the same day, a train arrived from Parkersburg with one company of the 11th W.Va. Volunteer Infantry. These men, along with several hundred home guards, were ready to protect the railroad bridges from destruction.

Confederate Forces Arrive

At 6:00 p.m. on May 6th, two groups of Confederate soldiers approached West Union, one coming north from Weston and the other coming west from Clarksburg, following the Northwestern Virginia Railroad.

Col. A. W. Harman of the 12th Virginia Cavalry, along with the 11th Virginia Cavalry and the 34th (Witcher's) Battalion Virginia Cavalry, were coming from Weston, and Col. Lunsford L. Lomax of the 11th Virginia Cavalry approached West Union along the railroad.

The raid, having started at 6:00 p.m., was over before dark. Several prisoners were taken on both sides and paroled that same day. Reports submitted to the War Department indicate that there were no deaths on either side, but according to the book The Jones-Imboden Raid by Darrell Collins, a Yankee deserter was killed in the fray. In the end, although two small bridges in Smithburg were burned, the main prize in West Union was saved by Union defenders.

Union Version of Skirmish

The following is what Union Col. George Latham said in his report to headquarters on May 18, 1863:

“Nothing of importance occurred here [West Union] until about 6 p.m. on the 6th instant, when two regiments of rebel cavalry made their appearance, driving in our pickets on the Weston and Clarksburg roads at the same time. They approached to within about 600 yards, as though they would attack, but a volley from our long-range rifled muskets caused them to fall back, and night soon coming on, which was very dark, they drew off having destroyed two small railroad bridges at Smithton, 3 miles east of West Union.”

Confederate Version of Skirmish

The following is what Confederate Col. Lunsford Lomax said in his report on May 30, 1863:

“Within a few miles of West Union, Captain Daingerfield was sent off to the right toward the Northwest Branch Railroad. The column moved on, an advance guard under Lieutenant [Edmund] Pendleton charging and capturing the enemy's picket, whom we found expecting us. We approached the town through a narrow gorge, precipitous and rocky on our right and low and swampy on our left. We found the enemy, 350 to 400 strong, drawn up in line on either side of the town. After occupying them in front until Captain Daingerfield had accomplished his object on the right, we withdrew, and were joined by Captain Daingerfield, who reported the destruction of the railroad bridges.”

Local Man Describes Skirmish

I have quoted many times from the diary of local pioneer, teacher and minister Flavius Josephus Ashburn (1832-1912). He wrote the following two entries in his diary in May 1863 about the Jones-Imboden Raid:

“The Doddridge Militia was called out last Saturday to guard West Union. I was not with them, for I have been discharged as unfit for military service in consequence of the deficiency of my eyesight. And I am informed that 400 soldiers came to West Union last night to defend it in case the Rebels should make an attack on it.

“I was informed today by the citizens of West Union and the soldiers that an army of rebels burnt the bridge below Smithton yesterday and cut the telegraph wires and captured a number of cattle and horses belonging to S.P.F. Randolph and others. They came in sight of West Union and the Union soldiers fired on them and they left - perhaps only to attack the town on the other side. They thought that there were about fifteen hundred of the rebel soldiers.”

West Union Described in Civil War

I had often wondered what West Union looked like during the Civil War, but since no photos are known to exist, I could only guess. However, I recently found a fascinating article on the subject in the October 4, 1862 issue of The Wheeling Intelligencer. The following is how one Union soldier described our county seat at that time:

“For the benefit of our friends in Wheeling and elsewhere, permit me to address you a few lines for publication in your ever welcome paper, giving you a short account of Company K, Captain Reese of the 6th [West] Virginia Regiment.

“Our company has been at Camp Wilkinson's, Clarksburg, since the 14th of September, but a great many reports having been in circulation lately concerning guerillas, horse thieves and other kinds of rebels doing pretty much as they please in Doddridge and Ritchie counties, and owing to these reports, Company K was ordered from Clarksburg to West Union to restore peace and happiness and Union men's horses to their homes once more.

“So we arrived here all safely on the evening of October 1st. It is the intention of the majority of our company, I believed, to break the backbone of rebellion in this part of Virginia, and Captain [John] Carroll, with 40 of his men, (who are stopping here with us,) and Lieut. Faris with the same number of Company K, are going to Glenville, thirty miles distant, on a reconnoitering expedition this morning.

“Captain Carroll, I understand, is perfectly familiar with the country he is going in, and if our reconnoitering party are not successful in breaking the backbone of rebeldom this time, I'll bet $2 if they find any Rebels on their route they will break the backbones of some of them.

“The report here is that the rebels are in strong force at Glenville, but I cannot ascertain their number, neither can anybody else. That's an impossibility. There might be 600 and there might be only six. So you can’t expect me to tell you how many there are. If I could, I would not hesitate an instant.

“I'll give you a few brief remarks concerning the town of West Union, where our company is encamped. Our tents are pitched near the Railroad Depot near the center of the place. If I were to tell you that West Union in Doddridge County was a pretty little place, I would then be telling you a lie and I don't want to do that. If I was asked to describe West Union I would answer: -- West Union, the capital of Doddridge County, is a dirty, dingy, dilapidated, dusty, one-horse town situated on the Middle Island Creek and the N.W.Va.R.R, surrounded by as uneven and rough a country as you will find anywhere in West Virginia.

“And now I must speak of our regimental hospital, now under the assistant surgeon Dr. John T Horton. The building is situated on an eminence above the town and there is continually a pleasant breeze about it, and plenty of good cool water convenient. I visited the hospital yesterday and I was surprised to find everything in such good order and in fine condition. Everything about the building and grounds is kept very clean and in splendid condition. What few are in it are doing very well. …”

Well, I must admit that “a dirty, dingy, dilapidated, dusty, one-horse town” was not exactly how I had envisioned our town back then, but at least we now have a pretty good idea of what West Union looked like in 1862, seven months before the Jones-Imboden Raid. I wrote in an earlier article about the Regimental Hospital being located in the West Union Academy building, which was situated on present-day Church Street directly facing Emmanuel Methodist Church. Apparently this was the cleanest place in town.

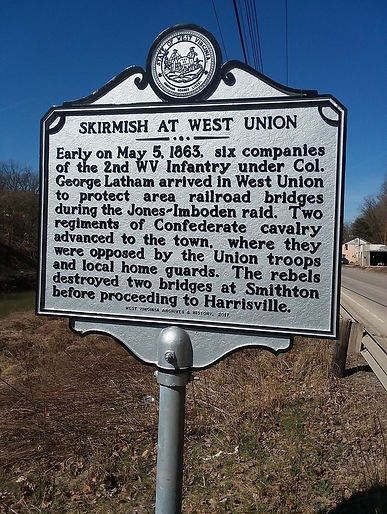

Historical Marker

In collaboration with the Doddridge County Heritage Guild, the West Virginia State Archives & History is making preparations to place a historical roadside marker in West Union to commemorate the Jones-Imboden Raid. In this way, an event that has long been but a footnote to history will be given the recognition it deserves. You can retrace the historical route that the Confederates took along the railroad by walking or biking the beautiful North Bend Rail Trail from Smithburg to West Union. The two bridges that you cross before you get to West Union are replacements of the bridges burned during the raid.

UPDATE TO JONES-IMBODEN RAID STORY

Carroll’s Barrels - The Trick that Saved West Union

Just when I thought I knew everything of importance about the Jones-Imboden Raid on West Union, up pops a piece of historical trivia that puts a whole new twist on it. This month marks the 155th anniversary of that raid, a skirmish which proved to be the only fighting that took place in Doddridge County throughout the Civil War. I wrote about the raid at length in this column last year. But there was one detail pertaining to the raid which I did not mention, simply because I only recently came across it. That "detail" was a stroke of genius on the part of a Doddridge County officer that confounded Confederate troops and was largely responsible for the favorable outcome of the engagement. To my knowledge, it has not been documented by Civil War historians, but it certainly deserves recognition.

On April 20, 1863 President Abraham Lincoln signed the proclamation that gave his formal approval for the admission of West Virginia as the 35th state of the Union, to take effect sixty days later. Immediately after that proclamation, Confederate forces, under the command of Brigadier Generals William E. “Grumble” Jones and John D. Imboden, embarked on a month-long raid through West Virginia aimed at disabling the B&O and other railroads, disrupting the Union government at Wheeling, and capturing horses, cattle and supplies. On May 6th, 1863, those forces entered Doddridge County, one of their primary targets being the railroad bridge over the Middle Island Creek in West Union. That bridge, which we now know as the one overlooking the dam near the football field, was the longest and highest train bridge on the Parkersburg branch of the railroad.

The Rebels' arrival in Doddridge County was by no means a surprise. The day before the raid, six companies of the 2nd W.Va. Infantry, under Col. George Latham, and one company of the 11th W.Va. Volunteer Infantry from Parkersburg, arrived in Doddridge to augment the several hundred local Home Guard under the command of Captain John Carroll.

Eye Witness Describes Raid

One of those Home Guard soldiers was Lewis M. Maxwell (1843-1934), who I profiled in a previous article titled "Rail Splitter of Willow Bend." He was a son of Franklin Maxwell and Frances Jane Reynolds. In 1932 Lewis M. Maxwell shared his memories of the Jones-Imboden raid in an interview with Wilbur C. Morrison. The following excerpts of that interview appeared in the February 21, 1932 issue of the Clarksburg Exponent-Telegram, which I came across in the Maxwell vertical file at the State Archives in Charleston:

"After the subject of the Civil War had been broached, Mr. Maxwell talked interestingly about the notorious Jones-Imboden raid through West Virginia and especially in Doddridge county. As a young man of 20 then, Mr. Maxwell was at an age when he realized what such a movement meant to the country and did not hesitate to give service as a member of the home guard in protecting people and property, although in justice to the raiders, they molested persons to a negligible degree."

Smithburg Railroad Bridge Burned

"Mr. Maxwell vividly recalls the raiders as they entered the West Union section of Doddridge county with the evident intention of capturing and looting the town.

"We heard of their marching in this direction when they left Weston, Mr. Maxwell said, as he talks about the raiders, and at home we were prepared for them when they arrived in this section. They crossed over from Weston, came down Meat House fork and burned the railroad bridge at Smithburg, just east of West Union.

"The raiders then circled back, came over onto Bluestone creek, passed down to where we now live to the Preston Fitz Randolph place just a little ways south of West Union and were confronted by a company of Union troops entrenched on a hill overlooking the valley which they had come down. They changed their mind and withdrew up the valley to the head of Bluestone creek, to the home place of my father.

"As they went down towards West Union, they tore the fences down as a measure to facilitate their retreat and so as not to depend entirely on the narrow road."

Clever Bit of Strategy

"A clever bit of strategy, Mr. Maxwell remembered, was employed by Capt. John Carroll who was in charge of the Union troops at West Union. The company took its position on what was afterwards termed Block House hill just east of town, and waited Jones’ advance down Bluestone creek. Carroll had obtained a number of empty flour barrels and so placed them along the front top of the hill as to make it appear to the raiders they were cannon and when the latter saw them they turned and hurried back up the creek without firing a single shot."

Raiders Take Cattle and Food

"Asked if the raiders confiscated any property, Mr. Maxwell said they drove away twenty cattle belonging to Randolph and used them as food, at least he knew of one they butchered on one of his father's farms and ate. As they took the others along, he presumed they killed and used them all as they needed them.

"The raiders went into camp right on my father's home at the head of Bluestone creek, Mr. Maxwell said. The officers occupied rooms in our home and my mother and a slave, 'Aunt Till,' cooked for and fed them.

"They gave Mother an order on the southern Confederacy for her to pay in addition to $25 in Confederate money, neither of which was of any monetary value. She kept the Confederate bills a long time as a reminder of their visit.

"The Raiders helped themselves to our corn, meat, hay, oats and the like and made fire out of fence rails. They arrived May 6 and left the next day. They ended up on another of father's farms, three miles to the southwest, where they killed and roasted the Randolph steer as already stated, passed over the south fork of Hughes river and went to Wirt county.

"When we received word that the raiders had left Weston and were headed in our direction, we kept close watch and drove our cattle and horses into the woods far away from the route of the raiders and kept them concealed until after they had come and gone."

Old Horse Left Behind

"We took 140 of our best cattle and twenty-one horses on to Pittsburgh and sold them as a precautionary measure.

"One of the officers as the raiders departed, following one night's camp 'to parch corn and fry meat,' as Mr. Maxwell expressed it, left an old horse tied to a sour apple tree on the Maxwell premises and someone, possibly one of the slaves, named the animal Jeff Davis. The horse, like the slaves, became a fixture in the family and that was all the recompense the elder [Franklin] Maxwell received for the property the raiders destroyed and the grain and meat they helped themselves to."

Carroll’s Barrels Save the Day

Let’s back up now to the “clever bit of strategy” described by Lewis M. Maxwell, an eye witness to the event. If you’re at all familiar with Blockhouse Hill across Middle Island Creek from West Union, and how it overlooks the train trestle and the road leading to it past the football field, you can easily imagine the scene. Captain John Carroll’s local militia would not have had the firepower or experience of regular Union infantry troops, so how were they to fend off the raiders and prevent them from destroying the railroad bridge, probably also the nearby covered bridge, and looting the town?

One way to keep the enemy from winning a battle is to discourage them from fighting it to begin with. And that’s exactly what John Carroll did. Whether planned in advance or a last-minute impulse, his placement of empty flour barrels along the front top of Blockhouse Hill was enough to make the Confederates stop in their tracks and abort the raid. Advancing quickly toward their target, and not being able to stop and analyze what they were seeing on the hill across the creek, the raiders were tricked into thinking that the barrels were cannon, and they wanted no part of an engagement against such heavy firepower. So the train trestle was saved, the covered bridge survived till the 1950 Flood, and the town was not harmed, all thanks to John Carroll’s barrels.

Captain John Carroll

On November 29, 1861, John Carroll was appointed Captain of the 6th (West) Virginia Regiment Volunteer militia. He mustered in as Captain of Co. M, 6th (West) Virginia Infantry on December 2, 1861 in West Union. He is described in the company descriptive book as being 5’ 11 ½” tall, dark complexion, gray eyes and dark hair. At some point in his military service, he incurred a broken leg and an injury to his chest. He mustered out in Grafton on December 1, 1864 upon expiration of service.

The resourceful Captain John Carroll was born in Preston County, (West) Virginia in 1826, a son of William Carroll and Lucinda “Lucy” Mott. A first cousin of renowned innkeeper Luke Jaco, he was residing in Doddridge County by the outbreak of the Civil War. He married Eunice M. Ball in 1854 and they raised a family of six children, his civilian occupation being farmer and butcher. John Carroll died in West Union on October 8, 1896, at age 68. His grave can be found at the top of the SDB section of Blockhouse Hill Cemetery, very near where his strategically placed flour barrels saved the day some 33 years before.

(NOTE: This article, written by Heritage Guild member Jennifer Wilt, originally appeared in The Doddridge Independent as part of her weekly column “Our Heritage: The REAL History of Doddridge County.”)